The election of François Hollande as president of France, by a 52-to-48 percent margin, will hopefully mark a turning point in the economic fortunes of Europe. Those concerned that Hollande’s victory and forthcoming policy shifts in favor of economic growth over budget austerity might put financial market stability at risk are mistaken. The new French president is no ideologue. On the contrary, he is a pragmatic progressive who realizes that austerity alone hasn’t worked, and that what Europe needs is a realistic strategy for job creation and economic growth.

This is precisely what Europe needs today. And a pragmatic, progressive, pro-growth agenda is what Hollande will pursue to deal with the continent’s slumping economies and government budget deficits.

Indeed, the election of Hollande compares to two historical precedents—Barack Obama in 2008 and François Mitterrand, the first socialist president of France, in 1981. Olaf Cramme at Policy Network, a London-based think tank that is at the hub of modernizing European social democracy, contrasts the ”era of hope” that saw President Obama elected to the one of fear that defines the Hollande victory. Much of Europe is back in recession, unemployment continues to grow, and the eurozone sovereign debt crisis seems to be spiraling out of control again. Yet when Obama was elected, he too was faced with a dramatic economic crisis, a financial system on the brink of collapse, and rising unemployment. In 2008, just like today, it was the candidate not the context that provided hope for a better future.

Perhaps the more telling comparison in the French context is with Mitterrand, until now the only socialist president in France’s history. Thirty-one years ago Mitterrand defeated the incumbent center-right president, Valery Giscard D’Estaing – the last time an incumbent president seeking re-election was defeated. Like the loser in yesterday’s election, Nicolas Sarkozy, Giscard D’Estaing had become increasingly unpopular with the French people – not least because of his adherence to liberal laissez-faire economics. Like Hollande today, Mitterrand promised a change to the economic agenda.

Unlike Hollande, however, Mitterrand tried to pursue a purely national policy of economic renewal, seeking to defend the inflated value of the French franc on the international markets and pursue an industrial policy of national champions. Ultimately he failed and embraced Europe as the route to resolving France’s economic woes and saving his own presidency. Interestingly, Francois Hollande was an early opponent of Mitterrand’s failed strategy and one suspects Hollande’s own approach today will be well informed by the lessons of that failure.

Hollande realizes that the policy options open to any one nation in a highly integrated European economic area are marginal. From day one of Hollande’s campaign, he has focused on Europe. Speaking at the Global Progress summit organized by the Center for American Progress in Madrid last October, two days after becoming the party’s nominee, he called for an end to austerity. As his campaign evolved he presented arguments in favor of a financial transaction tax in the eurozone to fund industrial-led growth, a renegotiation of the European Union’s fiscal pact agreed to in December – a pact that imposes overly tough fiscal constraints and European supervision on member state budgets – and the creation of eurobonds issued by the European central bank to mutualize the EU’s sovereign debt burdens.

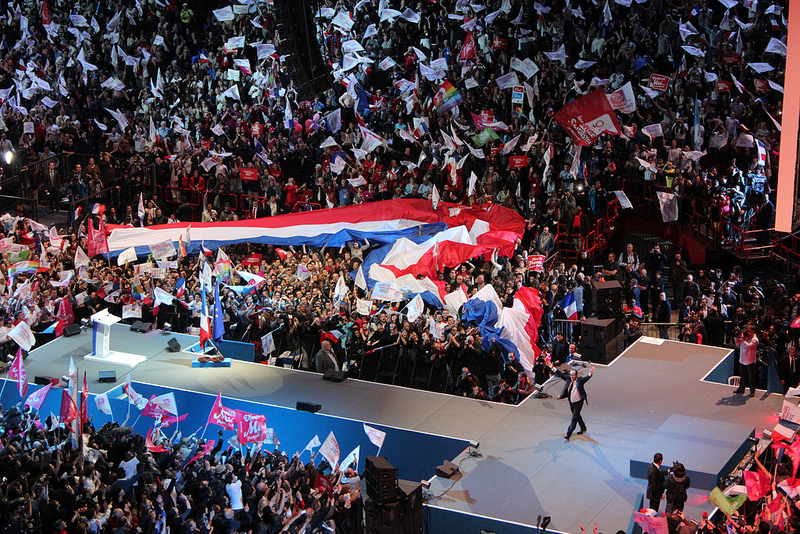

Speaking at the Bastille in front of his supporters on Sunday evening, Hollande said his victory was a ”message for all the people of Europe who, regardless of their leaders, want an end to austerity.”

Despite the rhetoric Hollande used to guard his left-flank during the presidential campaign, Hollande’s economic advisors pivoted back to pragmatism and began to sketch out a realistic European agenda in the runoff campaign against Sarkozy. As I noted in a recent column on the eve of the first round of the election, Elisabeth Guigou, former finance minister and advisor to Hollande, addressed a meeting of the progressive parliamentarians network co-organized by the Center for American Progress in Rome, where she suggested that rather than pursuing a burdensome renegotiation of the EU fiscal pact and eurobonds for mutualizing debt, Hollande would actually seek to complement the pact with a jobs and growth protocol at the continental level. She added that he would push for the creation of European ”project bonds” designed to leverage private capital into much-needed European infrastructure and industrial investment projects. Days later this vision was echoed by Annd Michel Sapin, another former finance minister advising Hollande, in an interview with The Financial Times.

Like President Obama four years ago, the expectations now resting on Hollande’s shoulders are unrealistically high and extend well beyond his national borders. And like in 2008 change today will take time. But by focusing on progressive, pragmatic, pro-growth policies, the new French president has set out a realistic and achievable vision of the Europe we need.

Matt Browne is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress, working on building transatlantic and international progressive networks. The article was first published at the CAP-website. For further reading, please see Matt Browne’s longer analysis ”Building a more prosperous Europe”. You can follow Matt on Twitter: @GlobalProgresMB.

Följ Dagens Arena på Facebook och Twitter, och prenumerera på vårt nyhetsbrev för att ta del av granskande journalistik, nyheter, opinion och fördjupning.